The disengagement -- the 2005 Israeli pullout from the Gaza Strip -- has been burned into the collective Israeli psyche as a national trauma. It remains an open wound. Many of the Israelis who were uprooted still refer to it as "the expulsion." In the span of eight days, 8,000 people were uprooted from their homes and 21 flourishing Gush Katif communities were turned into ruins. Glorious educational, religious and agricultural institutions that existed for 30 years became nothing more than bittersweet memories. The evacuators cried along with the evacuees as they ushered them away from their homes. The following day, Palestinians set synagogues on fire. In the years that followed, the ruins of the communities became Palestinian terror bases from which rockets were launched into Israel. The main objectives of the disengagement plan, as it was presented by its architect, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, were founded on security considerations. But these objectives were not achieved. The disengagement plan has failed the reality test: Hamas has grown stronger and taken over the Gaza Strip. Its operational capabilities have increased dramatically and it has turned into a small terrorist army. Today, 70% of Israel's population has been exposed to the threat of Gaza rockets (as far north as Haifa). Since the disengagement, 11,600 shells and rockets have been fired from Gaza into Israel. As early as September 2005, a month after the disengagement, the IDF launched Operation First Rain in response to heavy Qassam rocket fire from Gaza into Sderot. That operation was followed by Operation Blue Sky, Operation Lightning Strike, Operation Summer Rains and Operation Hot Winter. In more recent years, there were the three major operations -- Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), Operation Pillar of Defense (2012) and Operation Protective Edge (2014). The next operation, as everyone knows, is just a matter of time. In the 10 years that have passed since the disengagement, the number of politicians and defense officials who have apologized and sought to make amends for the move has risen higher and higher. Some expressed regret for the unilateral character of the plan while others lamented the expulsion itself or the residents' suffering. The government-appointed investigative commission appointed to assess the state's conduct concluded that it had failed in its handling of the evacuees. Public opinion, which initially supported the withdrawal, has also shifted: A vast majority of the population now views the disengagement as a failure. But despite all that, and after all the soul searching that was and will be, one question remains unanswered: What were the real circumstances that fostered the birth of the disengagement plan? Why was it ever hatched? Were Sharon's motives in executing it pure? Was it motivated by purely strategic, security related considerations, as his associates still claim? Or was it driven by personal and political interests? Was it designed to deliver the state of Israel from crisis or to deliver Sharon from the criminal investigations that were being conducted against him at the time? Perhaps the truth really is somewhere in the middle. Perhaps Sharon's legal troubles were only the backdrop for the decision, having only influenced its timing and representing only one factor among many that prompted Sharon to enact the disengagement. Even the answer to the question "who was Ariel Sharon-," which could elucidate the questions surrounding the motive, is under debate. Was Sharon -- a man who, for years, conducted himself as though he were the minister of the settlements, initiated the establishment of settlements, pushed to expand settlements and urged settlers to grab hold of the hills -- truly, ideologically committed to the settlement enterprise? Or was Sharon -- who withdrew Israelis from Yamit in Sinai, cooperated with the Wye River Memorandum and talked about a two-state solution decades ago -- actually a pragmatist in disguise? Perhaps there is some middle ground between the two Sharons, as Sharon himself contended. The idea to enact a diplomatic plan and withdraw from the Gaza Strip was not Sharon's. It was hatched long before, hovering in the political arena and gathering dust on the IDF shelves for at least 20 years before it was implemented. Even then, it included the evacuation of the Gush Katif settlements. During the election for the 13th Knesset in 1992, Likud minister Roni Milo advised then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir to promise to withdraw from Gaza if he should win the election. Shamir declined. Two years later, during Yitzhak Rabin's second term as prime minister, Israel left 80% of the Gaza Strip, leaving only Gush Katif intact in the southern part of the Strip in addition to a handful of isolated communities. Israel also held on to the Philadelphi route -- the buffer zone between Gaza and Egypt that was anchored in the Oslo Accords as a tool to ensure security. But in 1999, then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak asked his legal adviser on peace talks, attorney Daniel Reisner, for the first time to look into the legal implications of a full withdrawal from Gaza under a permanent agreement. Barak planned to withdraw from Gaza in the same way he withdrew from Lebanon, but he didn't have enough time to implement his vision -- his government collapsed less than two years after it was established. Two years later, Brig. Gen. Eival Gilady, then the head of the strategic planning unit in the IDF Planning Directorate, and Col. Danny Theresa secretly drew up a map that included a full withdrawal from Gaza as well as a number of settlements in Samaria. The document was named the Eidan map -- a mashup of the names Eival and Danny. The map was presented to the defense minister at the time -- Binyamin Ben-Eliezer -- and to Sharon, who was by then prime minister. It was presented as a unilateral plan, meant to generate a new reality. It was described as a stabilizing move. Sharon and Ben-Eliezer did not immediately embrace the plan, but they did not rule it out ,either. Within the IDF, a strong opposition to the Eidan plan began to emerge. What Gilady described as "stabilizing" and worthwhile, Brig. Gen. Yossi Kuperwasser, then the head of the research division in IDF Military Intelligence, defined as dangerous and irresponsible. He argued that the terrorists would view the unilateral withdrawal as an enormous victory for them, which indeed they did. When he was elected prime minister for a second time in 2003, Sharon was not the one who initiated the disengagement. His bureau chief, attorney Dov Weissglass, broached the subject with Sharon, setting the plan in motion with the international community, the Israeli political sphere and Sharon's closest advisers, including his two sons Gilad and Omri. Weissglass was the first to convince Sharon to go ahead with the disengagement. To review: Sharon did not think up the disengagement plan -- it existed long before he adopted it. He was, however, the one who decided to turn it from a theoretical idea into a practical plan, and to implement it. So what made him do it, after years of being viewed as the settlers' biggest advocate and partner? Until 10 weeks before the disengagement, Moshe Ya'alon was the IDF chief of staff. He took an active part in preparing and planning for the evacuation. But after his retirement from the IDF, in his book, he came out sharply against Sharon and his "true" motives. When asked about the accusations made in his book, Ya'alon, now the defense minister, stands behind his words, even more so now than he did then. "The negative turn in Israel's strategic position in dealing with the Palestinians was due to a wrong, inexplicable decision made by former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon," Ya'alon tells Israel Hayom. "I have no doubt in my mind that Sharon's decision was made for the wrong reasons. When he found himself in the midst of a personal crisis, because of the criminal investigations against him, and when his political popularity began slipping, Sharon decided to turn the tables and enact a dramatic measure that blatantly contradicted his worldview and did not line up with his perception of reality." Ya'alon believes that "In an effort to salvage his political future, Sharon put Israel on a strategic path with no purpose and no future. He may have convinced himself that he was doing something worthwhile for Israel, and that he would win some points in the international arena, but I can tell you unequivocally, having known Sharon, that the idea of the disengagement was foreign to him. It completely contradicted his way of thinking. The way that the idea came up was odd and the way it was handled was also odd." In his book, Ya'alon writes that Sharon never officially discussed the disengagement with him. He was only asked for his opinion on the evacuation of three of the settlements. Ya'alon claims that Weissglass tried to convince him to support the disengagement plan by saying that "Sharon's popularity is declining, so he needs to take action." (Weissglass denies having said this). "Sharon, together with his associates, observed the situation like a poker player," Ya'alon says. "He analyzed the advantages and the disadvantages of the other players and figured out how to make them work for him, to extricate him from his predicament both in the legal and the public arenas. The direct result of this analysis was the disengagement." Zvi Hendel's slogan Ya'alon was not the only one to feel that way. Even President Reuven Rivlin, then a Likud MK, voiced a similar opinion at the time. In 2006, Rivlin told Yedioth Ahronoth that Sharon had always been a pragmatist, adding that "the days of the decision on the plan were times of great personal distress for him. He made his personal considerations, and you can fill in the rest. I would suggest looking into what preceded his decision on the disengagement." "I suppose that historians won't have a very hard time figuring out this mystery," he said. Former MK Zvi Hendel, then a resident of the Gush Katif settlement of Ganei Tal, coined a catchy slogan to describe the situation: "A deep investigation yields a deep evacuation." Hendel still believes this. "It was not a guess or an analysis," he tells Israel Hayom. "I heard it directly from one of the members of the 'ranch forum' -- Sharon's closest advisers at the time." All the members of the so-called ranch forum, named after Sharon's Sycamore Ranch, have denied Hendel's allegation. Q: Why would anyone in the forum tell you that? Hendel: "I was close to one of them. He told me these things as a prophet, before it was done. He told me the crux of it, the plan to uproot all of us, and the real reason for it." Q: Why won't you say who it was then? Hendel: "If I expose him, he'll deny it." Q: What did you do with the information after he told you? Hendel: "I tried desperately to set up a meeting with Sharon. We were very close. True friends. But he didn't answer me. I left message after message until his secretary called me and told me the truth: 'Arik doesn't want to see you.' That is when I realized that the information I had received was true." Q: Did anyone else hear what you heard from a member of the forum? Hendel: "Yes. A rabbi from the south. But he won't talk, either." Similar allegations have been made on several occasions. Journalist Haggai Hoberman included in his book "Against All Odds" a transcript of an alleged conversation among the ranch forum advisers, in which Weissglass is quoted as saying "if the indictment [against Sharon] includes a bribery charge, we will be in deep trouble. We have to take a drastic step to avert the whole situation." Weissglass and Sharon's strategic adviser Eyal Arad both contend that the transcript is the product of Hoberman's wild imagination and that they never heard any of the forum advisers say anything of the sort. Journalists Raviv Drucker and Ofer Shelah (now a Yesh Atid MK) wrote in their book "Boomerang" that "behind the scenes, there were many, even among Sharon's most intimate confidants, who were convinced that the disengagement plan would never have been hatched if Sharon didn't need to avert the spotlight away from the investigations against him and his sons." Today, Drucker says that he doesn't have any evidence that the disengagement was prompted by the investigations, but "what I was able to say then, and what I can say today after reviewing the evidence, is that the way the process was conducted was influenced by the investigations against Sharon." Shelah explains that "no one heard Sharon say the words 'if I go with the disengagement, the media will protect me and the legal establishment will be on my side,' but without a doubt, his legal troubles were part of the atmosphere that led to the disengagement." A reminder: On the eve of the declaration of the disengagement plan, Sharon and his two sons were facing three criminal investigations. The straw companies affair, in which Sharon's son Omri was suspected of setting up fictitious straw companies to funnel money into his father's campaign while bypassing the campaign financing laws; the Cyril Kern affair, involving money alleged to have been illegally given to Sharon by the South African businessman, linked to the straw companies affair; and the Greek island affair, involving businessman David Appel, who was suspected of bribing senior government officials including Sharon to facilitate the purchase of the small rocky island of Patroklos to build a resort there. Does the chronological correlation between the Sharon affairs and the disengagement plan prove that there is a reason and a manipulator? Hendel and Ya'alon would say yes. But others are more careful. "The chronological link mainly gave a large portion of the public the feeling that it was not a coincidence," says researcher Anat Roth, who served as an adviser to a number of party leaders and has written the most comprehensive document on the Gush Katif residents' battle against the disengagement to date. This feeling was reinforced by the Israeli media, which went out of its way to protect Sharon in the lead up to the disengagement in an effort to ensure the implementation of the disengagement plan. Journalist Amnon Abramovich explicitly called on his colleagues to protect Sharon like an "etrog" (a citron, considered to be a very delicate fruit) "not only from the political threats but also the legal ones." Journalist Yoel Marcus wrote an article in Haaretz headlined "Corruption can wait." Among other things, he wrote that "Every so often, precious historic opportunities arise. When such an opportunity comes our way, we must stay in focus and not allow ourselves to be distracted by other issues, however important they may be." "Disengagement is this kind of formative episode to which Israel must give its full attention. The war on corruption is important, but it can wait. First let's see if we can get ourselves out of Gaza," he wrote. The investigations never worried Sharon Those who believe that the disengagement was motivated by legal trouble have not been able to present a smoking gun, only disconcerting circumstantial evidence. Sharon himself clarified in those days that "ideology is one thing and reality is another." It is my duty, he said, "to ensure Israel's existence with maximum security for the sake of the future." Sharon justified his decision with demographics and security considerations, and with a need to improve Israel's standing in the international arena. He said that during the course of his life he had made hundreds of thousands of decisions "many of them quite fateful, some of them life and death, but the decision to enact the disengagement was the hardest for me to make." "I am accused of taking steps that contradict what I say. That is flat out false. During the elections and as prime minister I have said explicitly that I support the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel. I am ready to make painful concessions in order to end the conflict between we who fight over the land," he said. Sharon consistently ignored the allegations against him that linked the decision to withdraw from Gaza to the investigations against him. Only once did he deviate from this stance, when he said in February 2004: "There is no correlation between the withdrawal from Gaza and the investigation. It is not because [of the investigation], it is despite of it." His friends thought then, and still do, that the accusations against Sharon were false and unfounded, and for the first time, they are returning fire. Eyal Arad says that the disengagement plan was presented to the ranch forum as Sharon's decision. "He didn't even ask our opinion," says Arad. "It was clear to me that the decision would immediately undermine his political footing among his supporters. I warned him. I told him honestly that he might not survive in the Likud Party and that he might lose his seat as prime minister." Q: Did any of you make the connection between the investigations and the disengagement? Arad: "The investigations never worried Sharon. He always said: don't touch that. Leave it to the lawyers. The entire theory that the investigations led to the disengagement is a complete fabrication." Q: Haggai Hoberman purports to quote individuals in the ranch forum as saying that there is a correlation. Hoberman, Hendel, Ya'alon and Drucker all allegedly quote Weissglass. Arad: "Hoberman never spoke with any of the six forum members. Weissglass, whom they quote, was never even a member of the forum. He appeared before the forum after Arik [Sharon] had already made the decision and instructed us to begin preparing public relations." Q: So everything is made up- Arad: "Maybe. Why not? After all, they needed to explain to themselves and to their constituents how it could be that the father of the settlements, the man that had worked together with them for years, came to change his views. They didn't believe that the real circumstances that Sharon encountered as prime minister were the reason for the change of heart. They needed to explain that it was bad so Hendel went for a conspiracy theory. Not only did the investigations have nothing to do with the plan, on the contrary -- Sharon consciously created a situation that could have led to him becoming politically isolated and ostracized." On February 2, 2006 the tension between Hendel and Arad peaked. Hended quoted Arad as telling one of the settler leaders that "the people hate you the same way they hate Arabs. My job is to make sure they hate you more than they hate terrorists." Arad denied ever having said this. He sued Hendel for defamation. Hendel recanted and apologized. He told the court that he had become convinced that Arad did not make the remark attributed to him by the settler leader. He promised to apologize publicly and Arad dropped the suit. Sharon's people say that Hendel's slogan "a deep investigation yields a deep evacuation" should also be taken with a grain of salt. I asked them why they didn't sue Hendel and they replied that "legally, only Sharon could sue." Weissglass, the man who explained, defended and put together the disengagement plan for Sharon, says that "any reasonable person understands that even the decision on the disengagement can't change the fate of investigations. No serious person truly believes that if the attorney general has evidence of crimes, it will be ignored because the person who allegedly committed the crimes initiated a diplomatic plan. [Former Prime Minister Ehud] Olmert had a diplomatic plan that was a thousand times more daring than Sharon's disengagement. Did that prevent an indictment against him-" Q: Defense Minister Ya'alon, who is considered a serious person, thinks to this day that the motives were personal. Weissglass: "That is nonsense. So are the quotes attributed to me suggesting that I linked the two things. It is completely false. Ya'alon was the first person outside Sharon's close circle to hear about the disengagement plan as it was taking shape. He cooperated from within the military with the preparations for the disengagement. He is still angry that his term as chief of staff wasn't extended." Q: So how did it happen that Sharon changed his opinion so drastically in such a short time? All of a sudden he realized that there were 1.5 Palestinians in Gaza? That the Jewish settlements there are an island in a tempestuous sea- Weissglass: "In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s Sharon believed that a dramatic demographic shift [in Palestinian territories] could bear diplomatic fruit, but when he arrived at the Prime Minister's Office he realized that this was a failure. He thought that if we continue to insist on having everything we could lose everything. In a sober, realistic view of reality, he changed his mind. The moment he realized that wanting everything could lead to losing everything, and that the only way to protect the majority -- meaning the large settlement blocs -- was to be diplomatically realistic, he understood that we would have to give up a large portion of the territory." Weissglass notes that a letter written by then-U.S. President George W. Bush, guaranteeing the status of the large settlement blocs under any future agreement, was part of the disengagement plan. "It was the reward that the administration in Washington had given us," he says. "It was unprecedented: it anchored American recognition of Israeli settlement blocs through legislation in Congress -- some 10% of Judea and Samaria -- and included an American declaration that Palestinian refugees would not return anywhere within Israeli borders." Q: What remains of that American pledge? Look at how Washington comes down on us for every apartment built in the settlements blocs or in Jerusalem. Weissglass: "I invite you to check how much we built in the blocs and in Jerusalem during those days, with full American approval. That really has changed, but it is Israel's fault. Bush's letter implied that everything outside the blocs goes to a Palestinian state. The moment Israel rejected that tenet, the other part of it, the commitment regarding the settlement blocs' status, and particularly the freedom to build there, was lost. These are two sides of the same coin." Q: The unilateral nature of the disengagement also wasn't exactly in line with the Ariel Sharon attitude. Weissglass: "The unilateral nature was dictated by the fact that by the end of 2003, [Yasser] Arafat was in charge of the Palestinian Authority, and in the wake of a terrible wave of terrorist attacks and two major attacks in Jerusalem, [then-Palestinian Prime Minister] Mahmoud Abbas asked to take a number of drastic measures against Hamas and was denied by Arafat. We weren't about to negotiate with Arafat, the crook and terrorist. But on the other hand we understood that something had to be done, that we needed change and hope and that treading water meant losing. The decision was unilateral because there was no other side. Arafat was the other side and at the end of 2004, when Arafat died, we began coordinating with the Palestinians before executing the plan." Q: In retrospect, considering today's reality, did the disengagement yield positive results? Was the disengagement not responsible for the grave deterioration in Gaza- Weissglass: "There is absolutely no connection. Hamas took over the Strip in June 2007, almost two years after the withdrawal from Gaza, in a violent military offensive. What is the connection between the disengagement and the Hamas revolution? How could a handful of communities in the crowded Gaza Strip prevented Hamas' armed takeover? The IDF hasn't been inside the cities, villages or refugee camps for years. They only surrounded the Jewish settlements to protect them. The IDF withdrew from the Strip in 1994 already." Q: Didn't the fact that Israel pulled out of the Philadelphi Route allow Hamas to arm itself with a larger number of rockets with far better range? When, before the disengagement, was there ever rocket fire from Gaza into Tel Aviv? Weissglass: "None of this has to do with the disengagement. Even when the IDF was present in the Philadelphi Route, they smuggled weapons through tunnels and by sea. The IDF didn't want to stay in Philadelphi after the disengagement. The only thing that would have happened if the disengagement had not been enacted is that today there would be thousands of settlers and soldiers in the middle of a death trap."

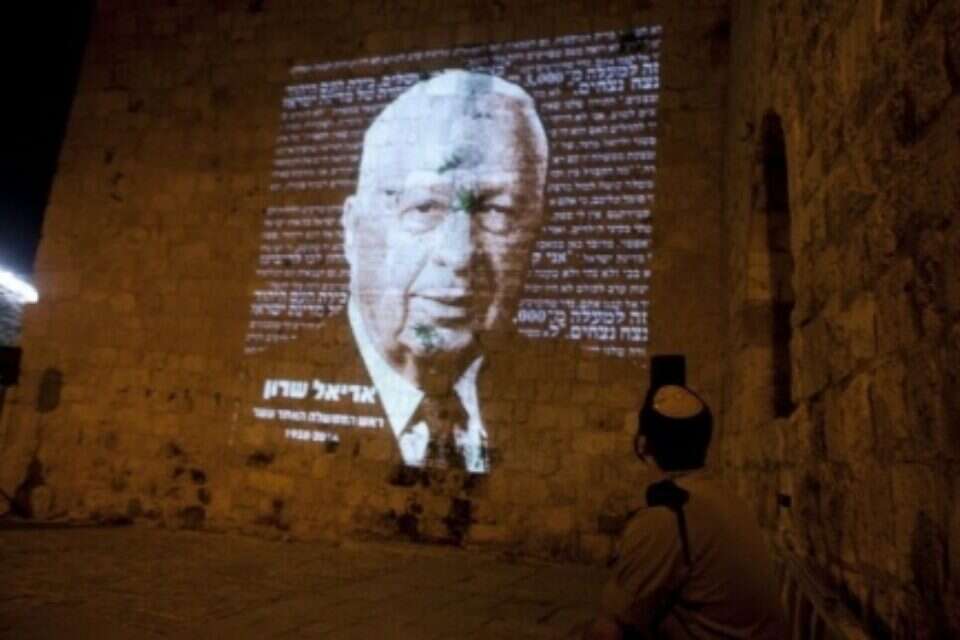

The secret of the disengagement from Gaza

For 10 years we've been talking about the 2005 Gaza pullout, the 11,600 projectiles that have been fired at us and the wars we've fought since, but one question remains unanswered: Did Ariel Sharon really believe the disengagement was good for Israel-